Bicarbonaturia

By Robert W Hunter

- 5 minutes read - 1049 wordsIn this post…

- The renal regulation of bicarbonate excretion

- The pathogenesis of proximal RTA

- The pathophysiology of vomiting

How is renal bicarbonate excretion regulated?

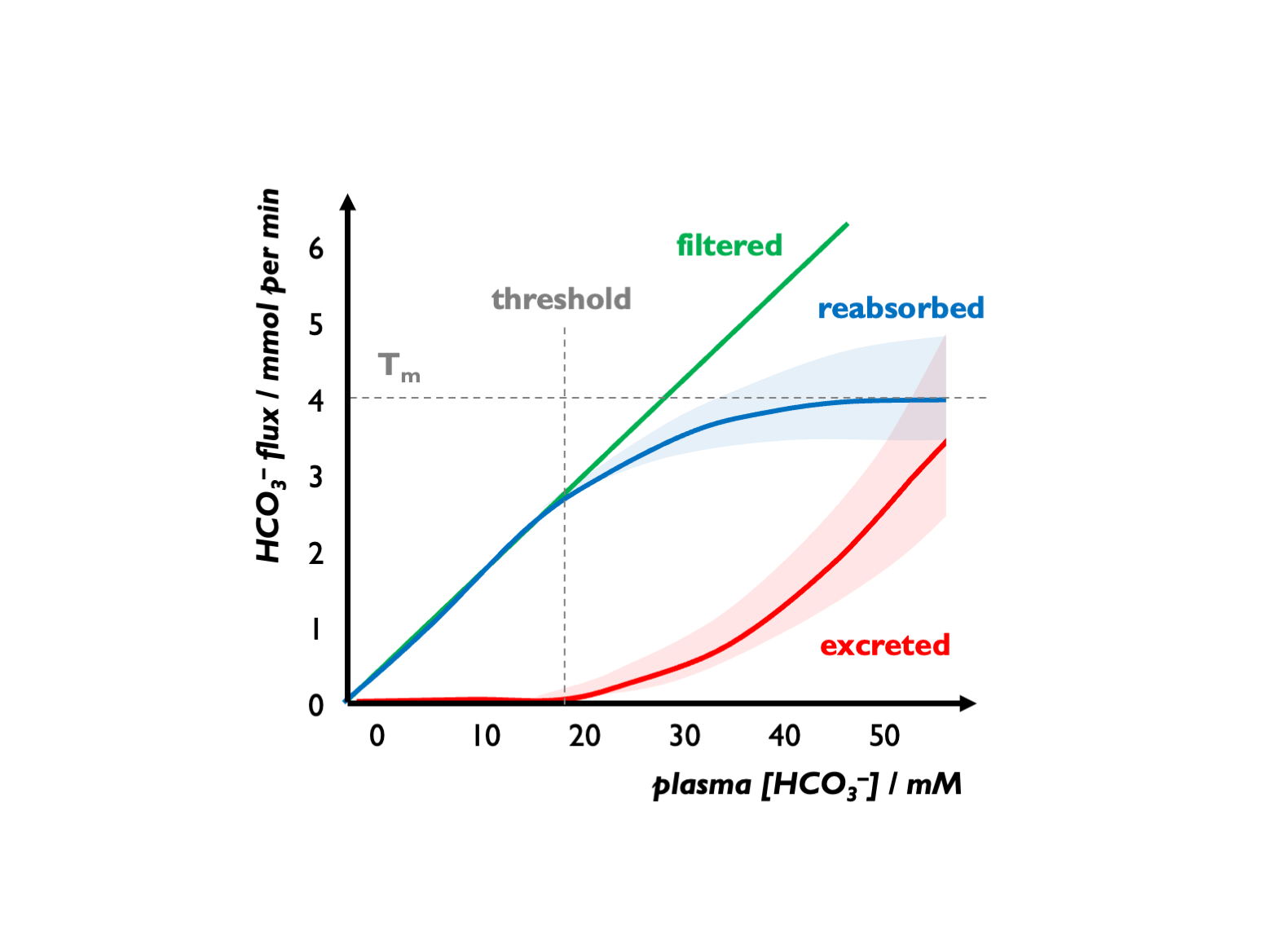

With respect to bicarbonate reabsorption, there are two key parameters to consider: the Tm = maximal rate of tubular HCO3 reabsoption and the renal bicarbonate threshold = the serum [HCO3] at which the filtered load exceeds Tm, and bicarbonate begins to appear in the urine.

There is an apparent Tm for HCO3-, setting a tubular threshold close to 25 mM but this is variable and influenced by various factors (GFR, luminal pH, hormonal factors etc.) For example, during volume depletion, stimulation of Na+ reabsorption (NHE activity) will increase HCO3- re-absorption, so leading to an increase in the apparent Tm for HCO3-. (See below for an explanation on why this is an “apparent” Tm.)

The pathogenesis of proximal RTA

The best way to think about pRTA is to view this as a reduction in the Tm for bicarbonate (and therefore renal bicarbonate threshold).

The mechanisms responsible for proximal and distal RTAs were investigated by Edelman and co-workers in 1967, and their explanation has not been bettered since (although our understanding of renal bicarbonate has been refined). They studied bicarbonate reabsorption in children during continuous NaHCO3 infusion, and H+ excretion in spontaneous acidosis and during treatment with NH4Cl.

H+ excretion was studied by measuring urinary pH. HCO3 reabsorption was studied by determining the Tm and bicarbonate threshold.

Healthy response

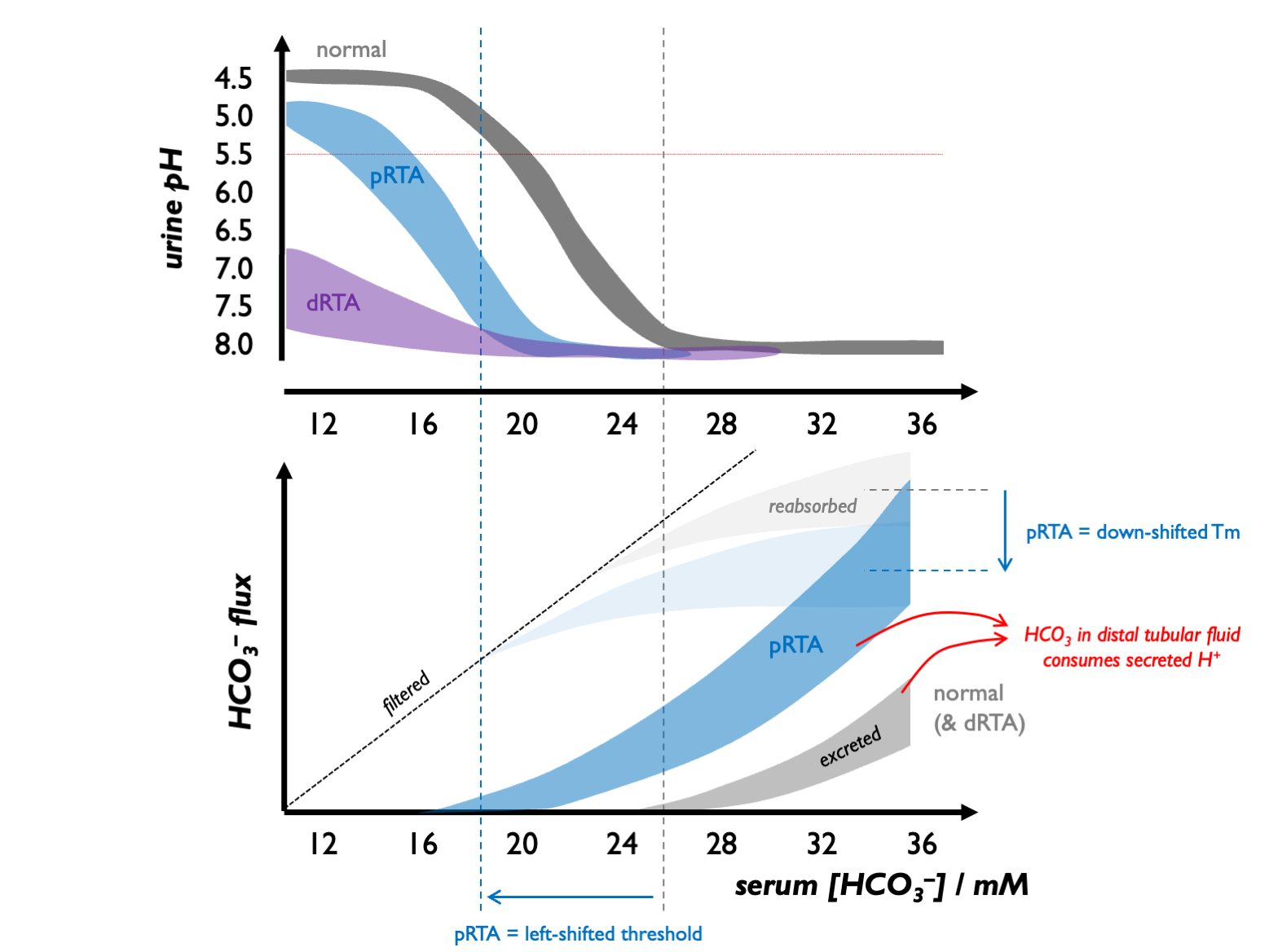

In healthy children, the renal bicarbonate threshold is 22 - 24 mM (and in adults, 24 - 28 mM).

Above this threshold, almost all secreted H+ is buffered by HCO3 in the renal tubular fluid - i.e. diverted to facilitating HCO3 reabsorption. A few mM below this threshold, sufficient H+ become available for acidifying urine and facilitating titratable acid and NH4 excretion. Therefore, the normal response to a metabolic acidosis is to generate an acid urine, so that when serum [HCO3] falls below 22 - 24 mM, the urine pH drops progressively from alkaline (7.5 - 8.0), reaching maximal acidification with pH << 5.5 when serum [HCO3] falls below 18 - 20 mM.

pRTA (type II)

In children with pRTA, there is a reduction in Tm and therefore in the renal bicarbonate threshold (to 15 - 20 mM). Therefore, when [HCO3] is in this range of 15 - 20 mM, there are significant quantities of HCO3 in the distal tubular fluid so that any secreted protons are buffered and the urinary pH remains alkaline. Once serum [HCO3] falls below the renal bicarbonate threshold, secreted protons are free to acidify the urine. Therefore these children can still generate acid urine (pH < 5.5 with high titratable acid and NH4 excretion) but there is a left-shift in the urinary pH-serum [HCO3] curve.

(In the original Edelman series, there was one exception who could not fully acidify the urine: a patient with Fanconi syndrome in whom hypophosphaturia limited the renal excretion of titratable acid.)

There is a homeostatic feedback loop inherent in a relatively fixed renal bicarbonate threshold: an alkaline urine is generated when serum [HCO3] rises; an acid urine is permitted as serum [HCO3] falls. This explains why blood pH settles at around the renal HCO3 threshold. Because acid excretion is still possible, the metabolic / skeletal phenotype in pRTA is never so severe as in dRTA.

dRTA (type I)

In children with dRTA, there is no change in the Tm or renal bicarbonate threshold. However, these children are unable to acidify the urine, even in the context of a profound metabolic acidosis. Urine pH is always >> 6.5 and there are markedly reduced rates of titratable acid / NH4 excretion. As they are in a state of constant +ve proton balance, they exhibit a profound metabolic / skeletal phenotype.

The pathophysiology of vomiting

The above simplistic model is helpful when understanding pRTA. However, it falls down in explanations of metabolic alkalosis. How can a metabolic alkalosis be sustained it excess HCO3 would simply be filtered and not reabsorbed as serum [HCO3] rises progressively above the renal threshold?

We should therefore refine our simplistic model in two ways:

the Tm for HCO3 would be better termed an “apparent Tm” because of course the urinary HCO3 content is determined not only by “spillover” from the PCT but also by HCO3 secretion in the CD (beta-ICs) and by H+ secretion (alpha-ICs);

the Tm for HCO3 (and by extension the renal HCO3 threshold) is not fixed; for example it varies in response to changes in volume status, GFR, luminal pH, hormonal signalling…

The pathogenesis of metabolic alkalosis, divided into generation, maintenance and recovery phases, was first described by Seldin & Rector in 1972. They point out that when large doses of HCO3 are administered to healthy individuals, this does not induce a metabolic alkalosis - precisely because the steady-state serum [HCO3] sits so close to the tubular threshold for HCO3. Therefore in vomiting / diuretic-induced alkalosis etc. there must be additional renal mechanisms to sustain the alkalosis. These mechanisms include:

- hypochloraemia and hence low distal tubular chloride delivery, impairing HCO3 secretion via pendrin in beta-ICs

- volume depletion leading to enhanced NaHCO3 reabsorption in the PCT

- volume depletion leading to RAS activation and enhance mineralocorticoid activity in the distal nephron (favouring electrogenic Na reabsorption with H+ and K+ secretion)

- hypokalaemia stimulating ammoniagenesis (and therefore HCO3 generation) in the PCT and altering expression of various PCT and CD transporters including pendrin to favour HCO3 reabsorption and impair HCO3 secretion

- increased distal delivery of Na+ (e.g. with loop diuretics) - favouring electrogenic Na+ resorption

The hypochloraemia / pendrin effect is likely dominant because chloride repletion has been shown to be necessary and sufficient for correcting metabolic alkalosis.

Clinical implications after vomiting

The clinical implications are that after vomiting:

- bicarbonaturia can drive renal losses of Na+ and K+ - leading to hypokalaemia…

- resolution of the alkalosis is only achieved by replacing chloride (e.g with generous IV NaCl)

There is the potential for confusion because UNa may be high (in contrast to other hypovolaemic states) and UK may be high (in contrast to hypokalaemia in the context of lower GI losses).

The test of choice, therefore, to differentiate between purging and salt-losing tubulopathy (e.g. in unexplained hypokalaemic alkalosis) is a urinary chloride; FECl is < 0.5% after vomiting.