Oh Mg (part 2)

By Robert W Hunter

- 5 minutes read - 984 wordsIn this post…

- Why does low Mg cause low K?

- Distal Na and K transport and the transepithelial voltage

Hypomagnesaemia: easy to find if you go looking for it; usually left well alone. (And often caused by a drug.)

But sometimes hypomagnesaemia is worth paying attention to if it is contributing to another electrolyte disorder such as hypocalcaemia or hypokalaemia. Any medical student can tell you that Mg deficiency can cause refractory hypokalaemia. But what is the mechanism? And why do we need to know the mechanism?

Why does low Mg cause low K?

Mechanism 1 - ROMK

Renal K+ secretion occurs predominantly through two channels: ROMK (mediating Na/K exchange in the distal nephron) and BK channels (mediating flow-dependent K secretion). Historically, Mg-depletion was thought to cause renal K wasting, predominantly because of its role in modulating ROMK channel function.

Like many other K+ channels, ROMK is inwardly-rectifying: that is, it allows K+ ions to flow into the cell more readily than out of the cell. This seems like an odd property for a channel that is primarily engaged in secreting K+ into the tubular fluid. So why has it evolved thus?

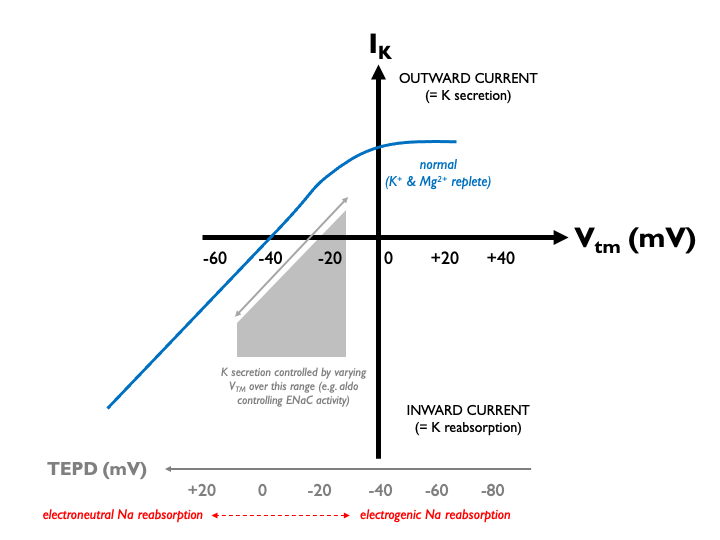

To understand that, we should first consider the critical role of the electrical driving force for K+ transport in the distal nephron. Potassium secretion in the distal nephron is regulated by the transepithelial potential difference (TEPD). This is, in turn, determined by sodium reabsorption through the epithelial sodium channel, ENaC. When sodium reabsorption is stimulated (e.g. by aldosterone), then the TEPD becomes more lumen-negative, favouring K efflux. When sodium reabsorption is inhibited (e.g. by amiloride) then the opposite happens: the TEPD becomes positive and K secretion is opposed.

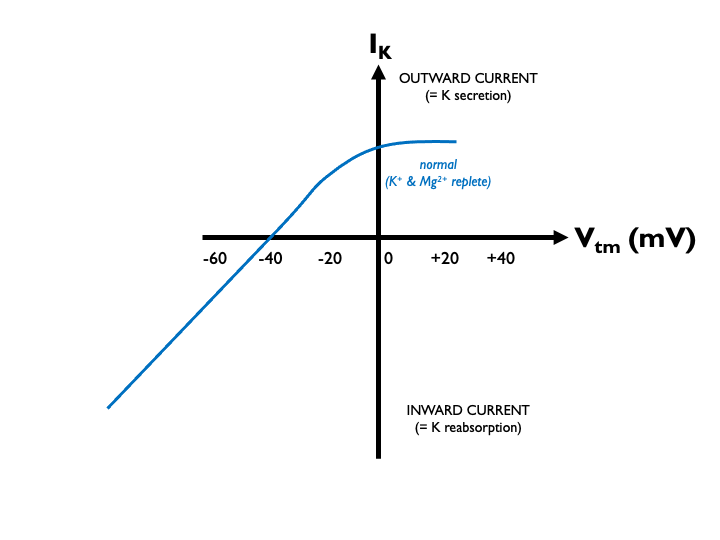

Let’s take a closer look, by considering the current-voltage relationship for ROMK. As this was first determined in Xenopus oocytes, current through the channel is usually plotted against transmembrane voltage, Vtm, the potential difference across the cell membrane. Vtm is typically negative: the interior of the cell is negative relative to the exterior.

I usually get confused at this point because of double-negatives. As the TEPD becomes more lumen-negative (e.g. in sodium reabsorption), the Vtm across the apical cell membrane becomes less negative as the cell-external and cell-internal potentials become closer. So when looking at these I-V plots, we must remember that a progressively negative Vtm equates to a progressivly less negative (or more positive) TEPD.

Under normal physiological conditions, K+ secretion is close to zero in the middle of the normal operating range of the TEPD (around -20 mV in the late distal tubule). Therefore aldosterone - via its effects on ENaC and the TEPD - can exert close control over renal K excretion:

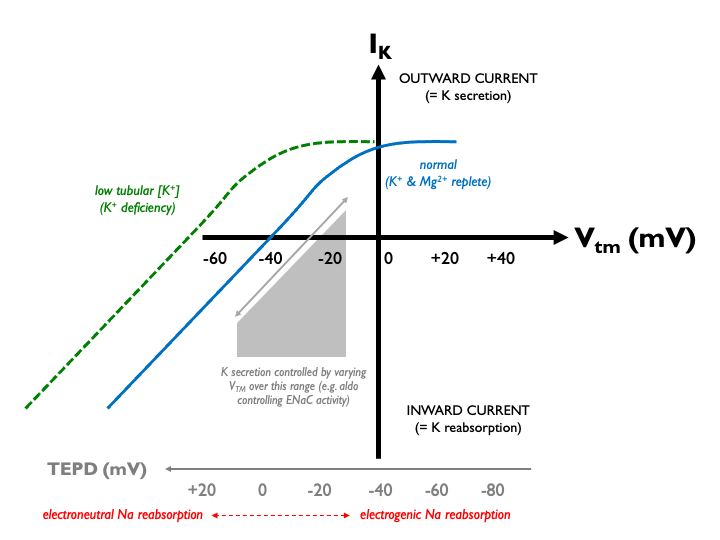

In K+ deficiency, the lumenal [K+] falls, so that for any given Vtm, the driving force for K+ efflux is increased. Therefore, the current-voltage relationship for ROMK shifts to the left:

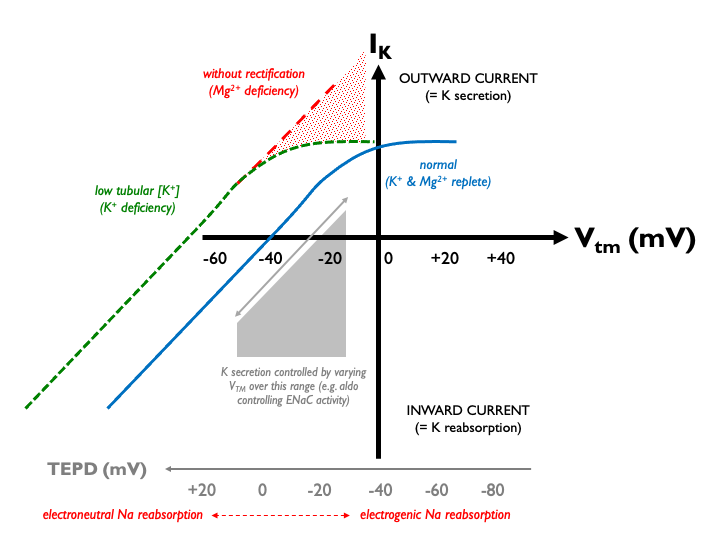

This could have the unfortunate paradoxical effect of driving unwanted K+ secretion. However, evolution has thoughtfully endowed ROMK with inward rectification in order that K+ efflux in this context is limited. And what is the mechanism of this effect? Enter Mg2+. At positive Vtm, Mg2+ ions bind to and block the channel pore. Therefore in profound Mg2+ deficiency, when this property is lost, ROMK channels are left open and K+ can flood out, exacerbating any pre-existing hypokalaemia:

Mechanism 2 - It’s the DCT, stupid!

So far, so good. That all makes sense. However, of course we now know that the main tubular player in determining net renal K excretion is not ROMK, but the thiazide-sensitive NaCl co-transporter, NCC. NCC sits in the distal convoluted tubule, upstream of ENaC and ROMK in the collecting ducts. First come, first served and so NCC activity determines the balance between electroneutral (K-sparing) sodium reabsorption and electrogenic (K-wasting) sodium reabsorption because ENaC can only act on whatever sodium NCC ‘leaves behind’ in the tubular fluid. NCC activity is therefore the knob that homeostatic mechanisms twiddle when attempting to achieve potassium balance. NCC activity (controlled by NCC phosphorylation) is modulated directly in response to changes in K homeostasis.

So wouldn’t any mechanism controlling renal K+ excretion be more likely to affect NCC activity? Well, it appears that this is indeed the case. Usually, K+ depletion stimulates expression and phosphorylation of NCC, for the reasons outlined immediately above. In the presence of Mg2+ deficiency however, this response is almost completely abolished (at least in rodents).

Summary

Sodium reabsorption and potassium secretion in the distal nephron are inextricably linked through the trans-epithelial potential difference (TEPD). Na+ reabsorption may be electoneutral (through thiazide-sensitive NCC) or electrogenic (through amiloride-sensitive ENaC). Electrogenic sodium reabsorption generates a lumen-negative TEPD, favouring K+ secretion through ROMK.

NCC sits upstream of ENaC and ROMK and therefore determines the balance between electroneutral and electrogenic sodium reabsorption. Accordingly, the physiogical response to perturbations in K+ homeostasis is directly targeted at NCC.

In K-deficiency, low luminal [K+] would increase the driving force for K+ secretion, potential exacerbating hypokalaemia. Mg2+ ions usually block ROMK in this circumstance, preventing excessive K+ efflux (inward rectification). This effect is lost in Mg deficiency. At the same time, Mg deficiency blocks the NCC activation that is usually observed in K-depletion.

Clinical implications

The main clinical implication is that one might want to check for - and correct - Mg deficiency in any treatment-refractory hypokalaemia. There is also an implication for how we interpret urinary electrolytes in combined Mg2+ and K+ deficiency. When faced with hypokalaemia, there is a reflex urge to check urinary [K+] and perhapps even calculate a TTKG. However, in the context of Mg2+ deficiency this could be misleading, because we now know that whatever the initial cause of the K-depletion, there is likely to be urinary K-wasting because of the Mg-deficiency. Better, therefore, to rely on clinical judgement to work out the likely cause and defer any urinary electrolyte testing until after the Mg2+ deficiency has been corrected.