Curvilicious

By Robert W Hunter

- 4 minutes read - 813 wordsIn this post…

- The Brenner hypothesis

- Tubuloglomerular feedback & glomerulotubular balance

- How SGLT2i affect glomerular haemodynamics

- How loop diretics effect glomerular haemodynamics

The importance of intraglomerular pressure

At the cornerstone of contemporary treatments to delay CKD progression are agents (RAS inhibitors and SGLT2i) that reduce intraglomerular pressure. Whether or not this effect is the most important mechanism of nephroprotection is open to debate - particularly for SGLT2i. However, it is at the very least likely to be a central mechanism.

Intraglomerular pressure correlates with single nephron GFR - not a parameter that we measure routinely in the clinical setting. In diabetic kidney disease in particular, it is well recognised that in the early phases of the disease, overall GFR is preserved despite nephron loss, necessatating increased snGFR in at least a subset of remaining nephrons.

The concept that high intraglomerular pressure might cause glomerular injury and progressive CKD was first popularised by Barry Brenner and colleagues in the 1980s.

Tubuloglomerular feedback and glomerulotubular balance

snGFR is held reasonably constant by tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF): an important homeostatic mechanism that stablises delivery of solute to the distal renal tubule.

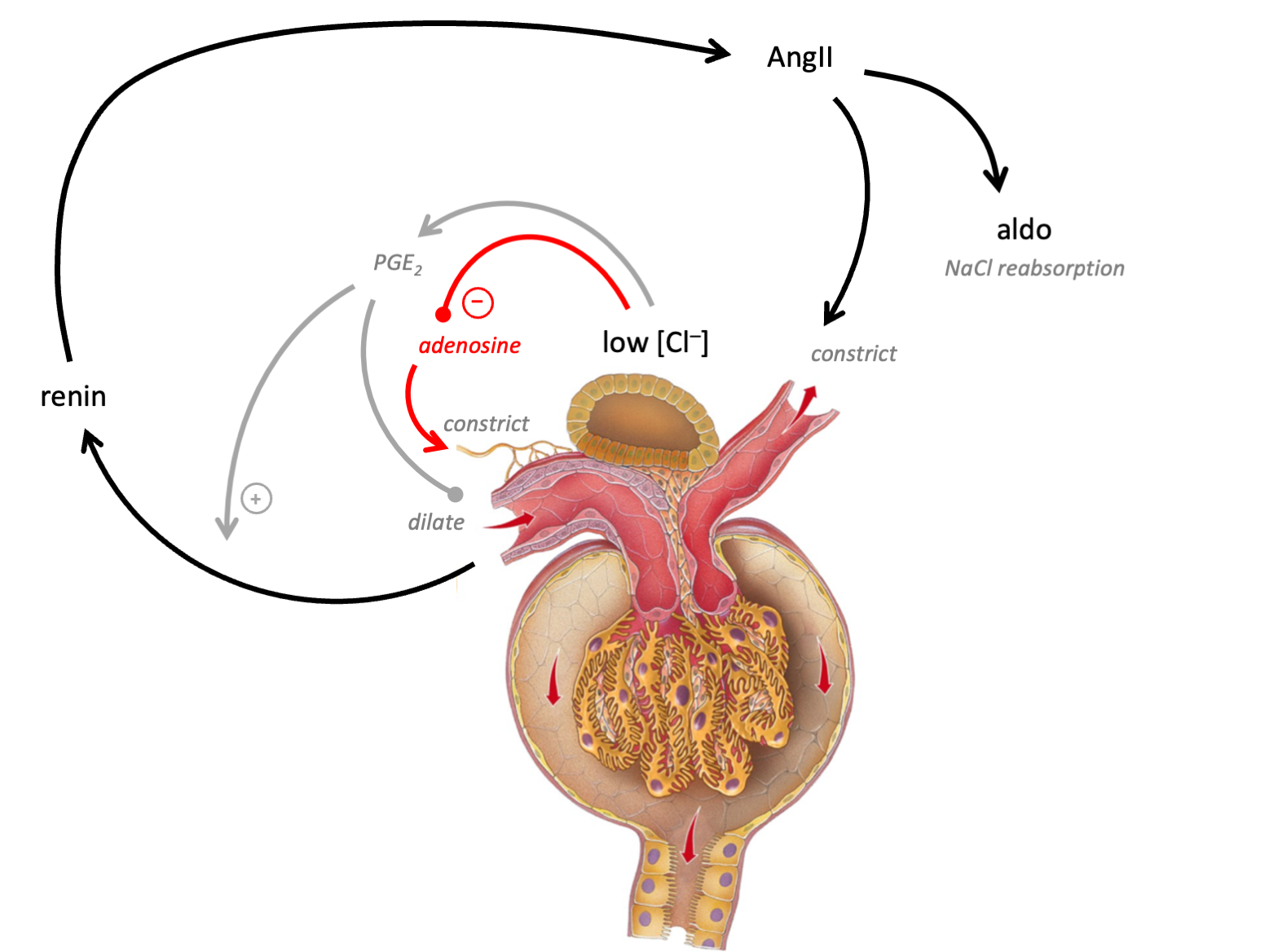

In brief, luminal [chloride] is sensed at the macula densa. Low levels stimulate PGE2, which in turn triggers renin synthesis - resulting in diltation of the afferent and constriction of the efferernt arteriole (so raising intraglomerular pressure). High levels trigger release of adenosine, resulting in constriction of the afferent arteriole (lowering intraglomerular presssure).

The macula densa is ideally positioned to act as a sensor of systemic volume status. Reabsorption of tubular fluid is isosmotic in the proximal tubular but solute is reabsorbed independently of water in the “diluting segment” - starting with the TALH. Thus, whereas luminal [NaCl] remeains relatively constant throughout the PCT, by the end of the TALH, it varies in proportion to tubular flow rate (due to glomerulotubular balance - see below).

Therefore the juxtaglomerular apparatus serves at least three functions:

an

autoregulatoryfunction, maintaining reasonably constant snGFR and distal solute delivery (note that this function is anti-homeostatic with respect to systemic sodium homeostatis because it would promote increased net glomerular filtration in response to volume depletion);regulation of systemic

volume homeostasis: if many nephrons are sensing low tubular flow rates, then the net effect of increased renin production will serve to preseve glomerular pressure and stimulate NaCl reabsorption; anda

defenceagainst life-threatning volume loss in the event of acute tubular injury (so-called “acute renal success”).

It is probably the most elegant example of how evolution can give rise to simple but devastatingly effective physiological control mechanisms.

Glomerulotubular balance (GTB) refers to the phenomenon whereby tubular reaborption varies in proportion to tubular flow rates. This is a direct consequence of the stochastic nature of solute reabsorption by channels and transportes in the apical cell membrane.

What about the curves?

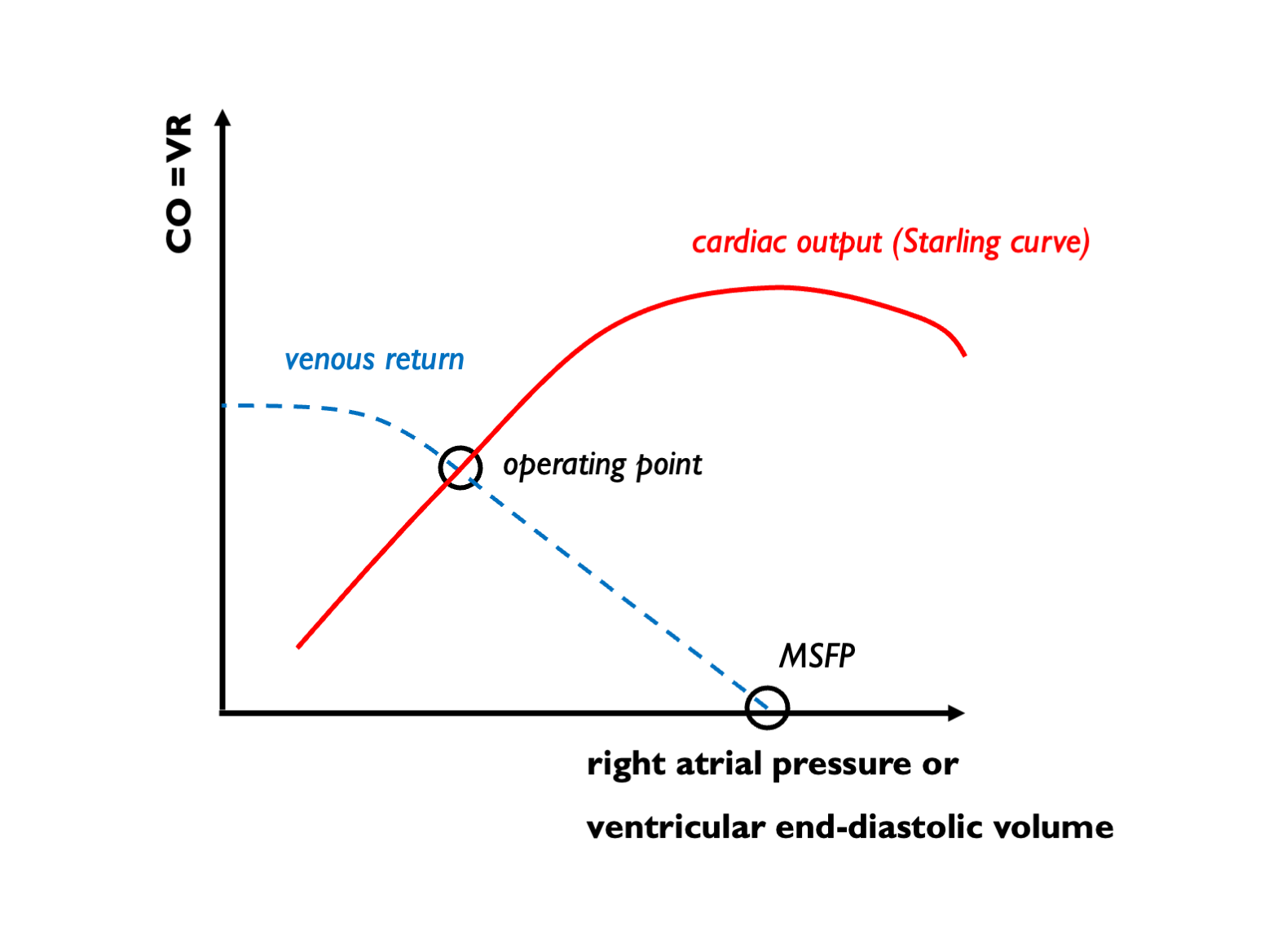

The best way to visualise this process is to draw GTB and TGF curves and see where they intersect. This sort of analysis will be familiar to anybody who has looked at Guyton’s intersecting venous return and cardiac function curves:

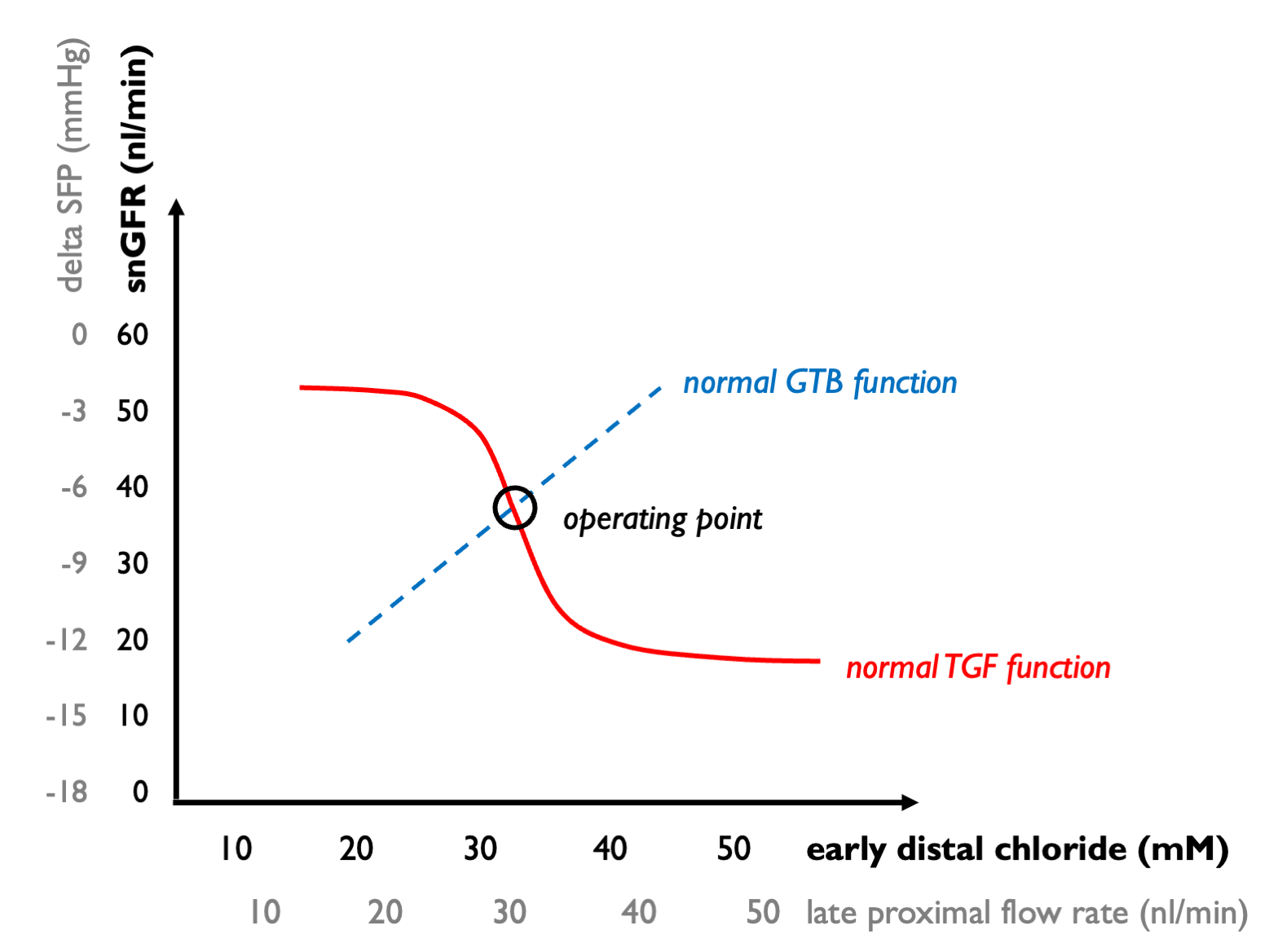

In this case, we need to plot GTB and TGF curves together. GTB describes the extent to which distal solute delivery varies as snGFR changes; TGF describes how snGFR changes in response to distal solute delivery. The operating point lies at the intersection of these curves:

Now we can ask how these processes are modified by disease and drugs.

Now we can ask how these processes are modified by disease and drugs.

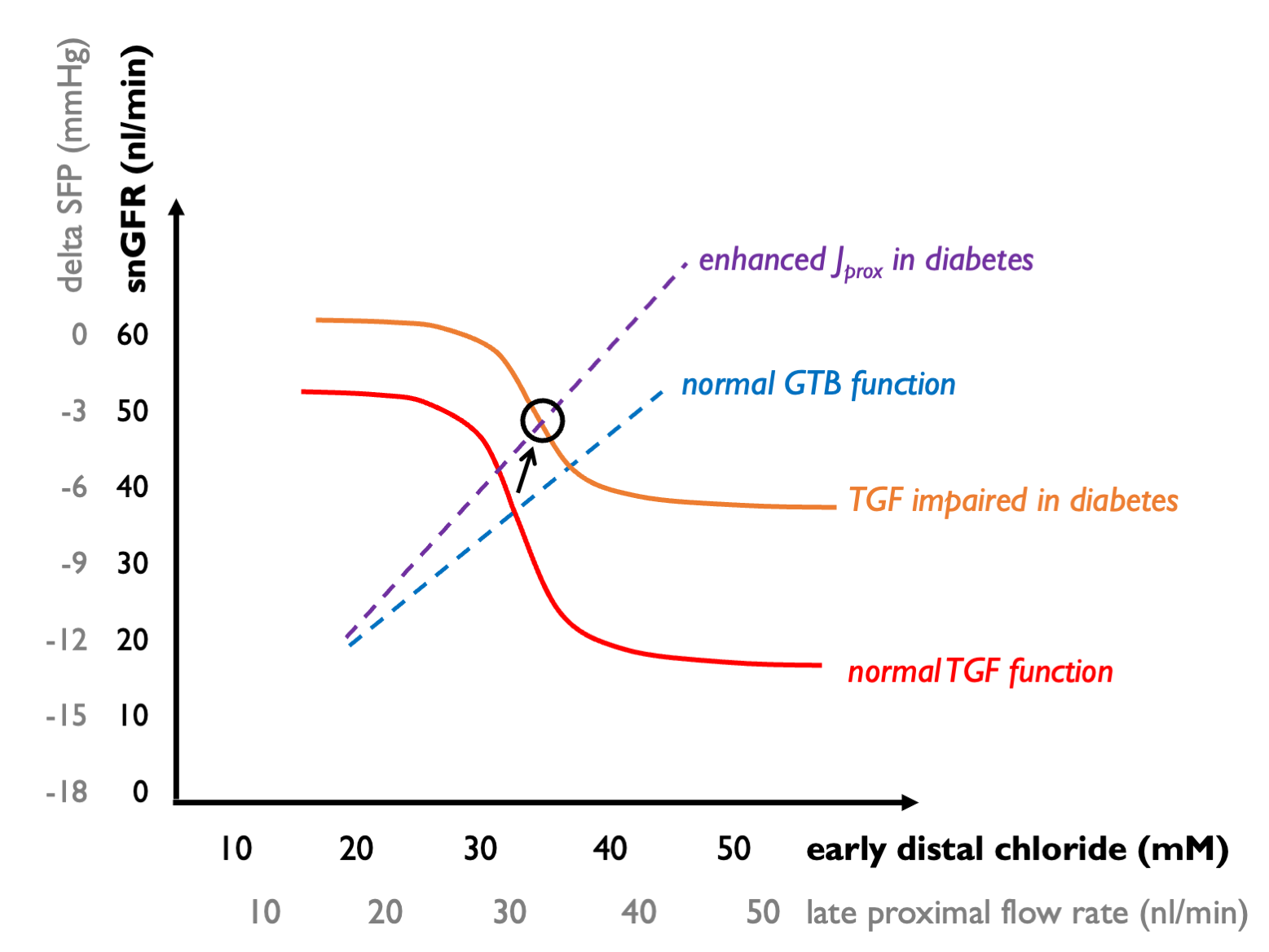

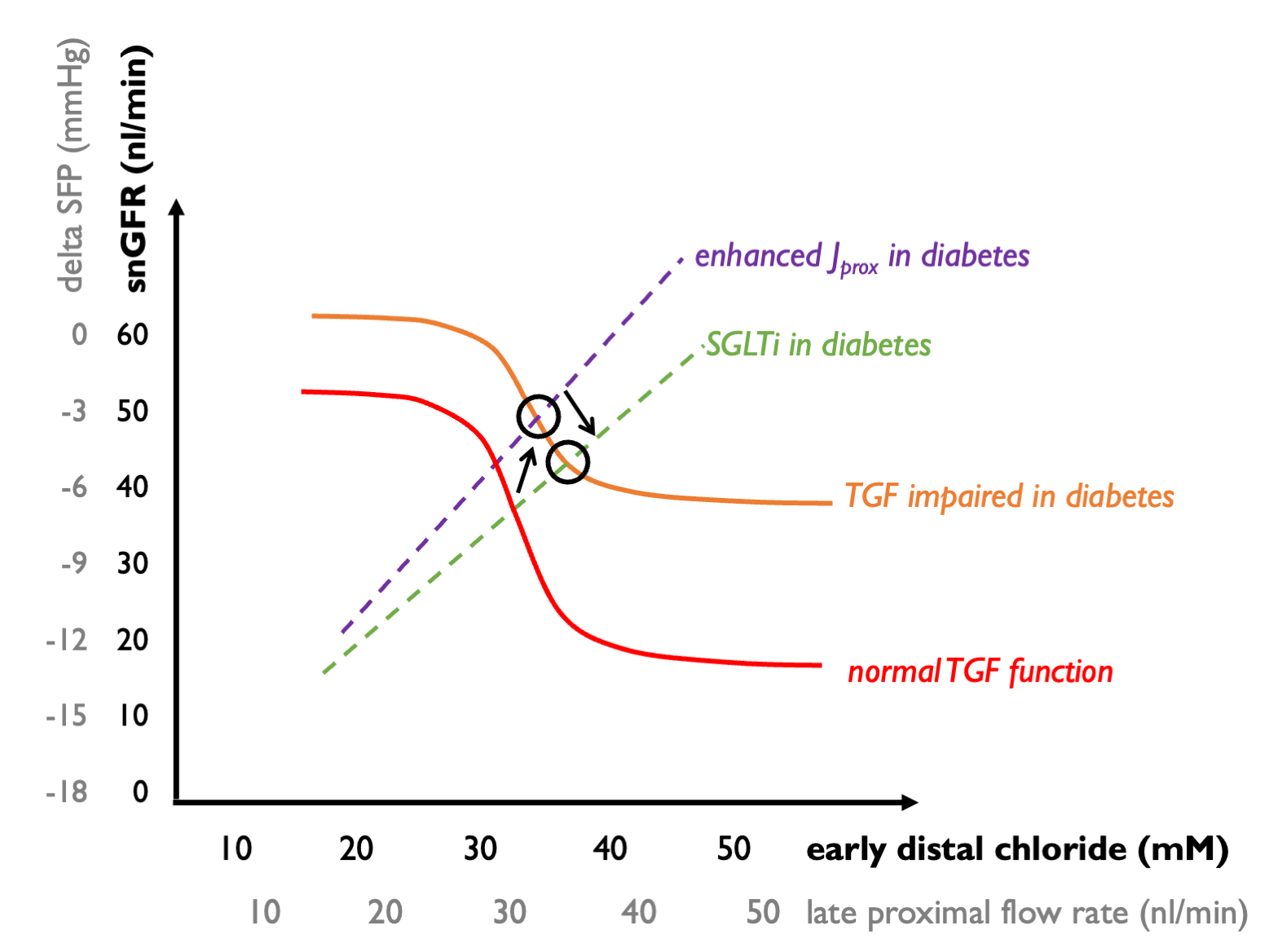

In diabetes, we see:

enhanced proximal reabsoroption of solute (driven by enhanced Na-glucose reabsorption with increased filtered glucose loads) - this blunts the GTB curve, giving rise to an upward shift in which each increment in snGFR gives rise to relatively less of an increment in distal solute delivery; and

relative insensitivity of the TGF mechanism. (The mechanism of this effect may be complex but could in part be explicable by hyporeninaemia - hence less AngII mediating efferent vasoconstriction.)

As a result, the operating point shifts upwards - leading to raised intraglomular pressure (higher snGFR).

SGLT2 inhibitors, by restoring proximal solute reabsorption back towards normal sensitise the GTB curve - giving a downward shift (so that every increment in snGFR gives rise to more of an increment in distal solute delivery). Thus snGFR returns towards normal levels, at the expense of increased tubular flow rates. (This “expense” may be beneficial if the resulting natriursis helps to control volume overload and hyperkalaemia in heart failure or CKD.)

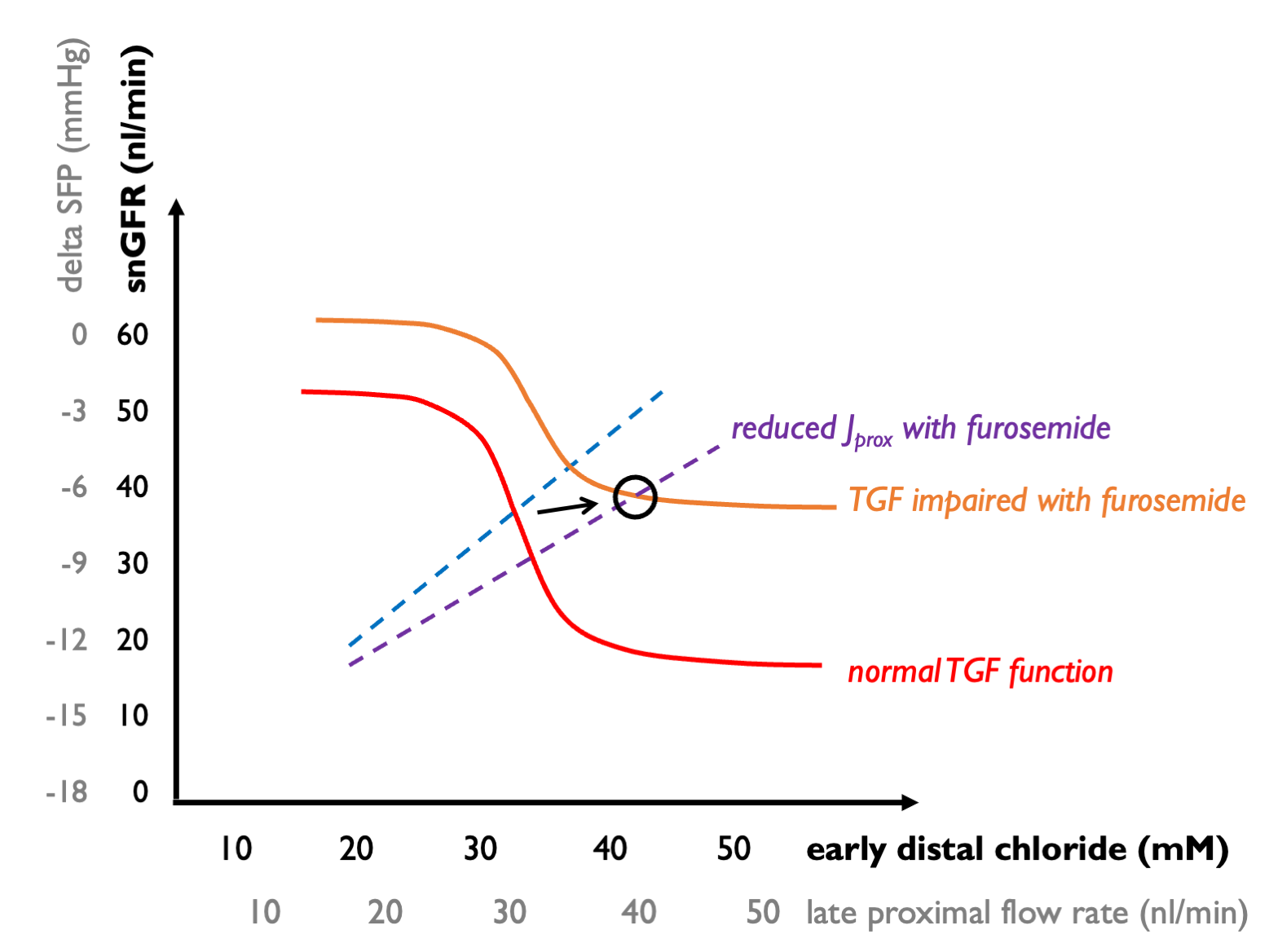

But what about other drugs? Furosemide is an interesting case. This should simultaneously shift the GTB curve down (for the same reasons as SGLT2i) and shift the TGF curve up and to the right, if it blocks NaKCl entry into macular densa cells (thus impairing the sensing to tubular [Cl]).

As a result, tubular flow rates will increase without much of a change in snGFR (or net GFR) - which is what is commonly observed in the clinic.

As a result, tubular flow rates will increase without much of a change in snGFR (or net GFR) - which is what is commonly observed in the clinic.