Should I stop the furosemide?

By Robert W Hunter

- 6 minutes read - 1112 wordsIn this post…

- What effect do loop diuretics have on renal free water clearance?

- Should we stop furosemide in hyponatraemia?

- Why do we need to restrict water intake when giving furosemide in hyponatraemia?

We are mostly water and rapidly run into trouble when we become under- or over-hydrated. We could argue, therefore, that one of the kidney’s most important jobs is that of maintaining water homeostasis. It is surprising that we are able to mess around quite profoundly with this process without running into trouble more frequently than we do. Among the millions of patients who take diuretics, only a minority develop significant problems with water homeostasis.

But when they do, it can be tricky to get one’s head around exactly how diuretics interfere with water homeostasis. Thiazide diuretics are easier to understand in that they invarably exacerbate hyponatraemia. (Although their paradoxical anti-diuretic effect in diabetes insipidus is still a head-scratcher and will be the subject of a post here in the near future.) Loop diuretics, on the other hand, can act to promote or oppose free water excretion depending on the prevailing physiological circumstances. So how do we explain that?

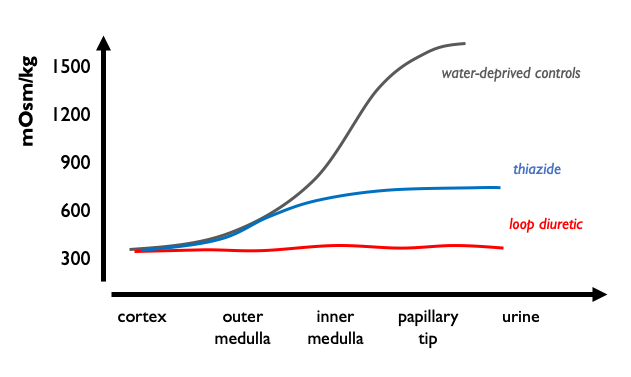

Working from first principles

A good starting point is to consider the water permeability of the different nephron segments. Experiments conducted in isolated perfused rabbit tubules showed us that the water permeability is exceedingly low in the ascending loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule. Therefore thiazide and loop diuretics – by inhibiting sodium transport in these segments – prevent the generation of free water in the luminal fluid and reduce the ability of the kidney to excrete free water. The reason that loop diuretics can have opposing effects on water excretion is that they also act to prevent the corticomedullary osmolality gradient from being established, thus removing the osmotic drive for AVP-dependent water reabsorption. So they also stop the kidney from generating a concentrated urine. As a result they tend to induce isothenuria: a urine osmolality equal to that of plasma.

Loop diuretics impair the ability of the kidney to generate a dilute or a concentrated urine. So in a patient who has just ingested a water load and is generating a dilute urine (UOsm < 300 mOsm) loop diuretics will raise urine osmolality and oppose free water excretion, potentially exacerbating hyponatraemia. However in a patient undergoing antidiuresis (UOsm > 300 mOsm) they will lower urine osmolality and promote free water excretion, potentially correcting hyponateamia.

Why furosemide must be combined with fluid restriction in hyponatraemia

Furosemide paralyses the kidney’s ability to control free water excretion. As the kidney is then unable to generate a dilute urine, any excessive free water load will inevitably result in hyponatraemia. So how much should we restict water intake in a patient taking furosemide if they develop hyponatraemia? This will obviously depend on solute intake / insensible losses etc. But lets assume – for the sake of argument – that we have a 60 kg patient in whom there is a net daily gain of 100 ml insensible free water (300 ml metabolic water generation plus 600 ml in food minus 800 ml lost through the skin and respiratory tract) and a dietary solute intake of 600 milliosmoles per day. The 600 milliosomoles will be excreted in 2L of isothenic urine (UOsm 300 mOsm); if we deduct 100 ml to offset the net insensible free water gain, we arrive at a daily water allowance of 1.9L. Such a patient, taking furosemide, will develop hyponatramia when water intake exceeds this threshold. That may not be so hard to adhere to, but of couse this threshold will be significantly lower in many patients - e.g. those on a carbohydrate-rich / solute-poor “tea and toast” diet. (Fortunately most patients on loop diuretics also adhere to fluid restriction so that hyponatraemia is a relatively infrequent outcome.)

Using the “Furst ratio”

In the above preamble we rather lazily defined urine concentration in terms of osmolality. Strictly speaking, we may be better to define urine concentration in terms of the electrolyte content rather than osmolality per se. As urea is an ineffective osmole with respect to most cell membranes, it is usually said that when assessing the impact of kidney function on plasma tonicity, one would be better to look at the urine electrolyte content rather than urine osmolality. The calculation of electrolyte-free water clearance can be cumbersome and therefore it is quicker at the bedside to calculate the Furst ratio. Very crudely speaking – in the context of hyponatraemia – when the sum of the concentrations of urinary Na and urinary K exceed that plasma sodium concentration, water intake must be restricted very aggressively (to around 500 ml per day or less) in order to treat hyponatraemia. Under these circumstances – given that the urine the urine is so concentrated – starting furosemide ought to increase free water excretion in the urine.

Does this work in practice?

That is all very well in theory, but is there any empirical evidence that furosemide can help to correct hyponatraemia? The recent EFFUSE-FLUID randomised controlled trial compared three treatment stragies in patients with SIADH: fluid restiction alone, fluid restriction plus furosemide and fluid restriction plus furosemide plus oral NaCl supplements. Rather disappointingly, there was no difference in the rate of plasma sodium correction between the three groups (and an increased frequency of hypokalaemia in patients randomised to furosemide). This was a well designed study in an area that is sorely lacking in randomised controlled trials (and definitely NOT lacking in papers extolling the theoretical virtues of furosemide). So it is very welcome - and probably tells us that furosemide is not necessary in most patients with SIADH. However, it does not mean that we should never use furosemide in the treatment of hyponatraemia. For one thing, loop diuretics are obviously helpful in the context of hyponatraemia in oedema. And loop diuretics may still have a role to play in some patients with SIADH. The majority of patients in the EFFUSE-FLUID trial did not start with particularly concentrated urine (60% of patients in furosemide groups had Furst ratio < 1) so may not have been likely to benefit from furosemide therapy. (And there are a few other limitations: the open-label design, once-daily low-dose furosemide, relativey low dose) of supplemental NaCl, no potassium supplements etc.)

The bottom line

Furosemide will exacerbate hyponatraemia in the context of excessive water intake / dilute urine. Furosemide should help to correct hyponatraemia in the context of a concentrated urine (UOsm >> 300 mOsm; UNa + UK > PNa) - but must be used along with a water restriction. Many patients with SIADH will respond to water restiction alone.