Terlipressin and hyponatraemia

By Robert W Hunter

- 6 minutes read - 1237 wordsIn this post…

- The evolution of the vasopressin system

- How can one hormone regulate two physiological parameters (tonicity and blood pressure)?

- Why does terlipressin not always cause profound hyponatraemia?

“Thousands have lived without love, not one without water.”

— WH Auden

Does terlipressin cause hyponatraemia?

We had a patient with hepatorenal syndrome on the unit recently. Her sodium was 125 mM and I found myself wondering - as I always do in such a patient - whether terlipressin could be contributing. It was a prompt to review the pharmacology of vasopressin. But first, it was useful to first consider how the vasopressin system evolved to regulate two independent parameters: vascular tone (the effect that terlipressin aims to exploit) and extracellular tonicity.

Evolution of the vasopressin-kidney axis

Elsewhere in the universe, silicon- or cyanide-based chemistries could form the building blocks of alien life-forms, but on our blue planet life developed in water. It is not surprising then that water control mechanism arose very early on in the evolutionary course of multicellular organisms - far before the emergence of the vertebrate kidney. Water conservation became a priority as the early freshwater fishes moved to terrestrial and salt-water environments. Thus, an ancestral antidiuretic hormone arose prior to the divergence of vertebrates and invertebrates ~700 million years ago and lives on in lower vertebrates as arginine vasotocin.

In humans, the predominant physiological role of arginine vasopressin is to fine-tune free water excretion in the renal tubules. The vasopressor function for which this hormone is named only manifests in extreme states such as hypovolaemic shock. However, it is actually the vasopressor function that arose first in evolution.

It seems likely that the ancestral vasotocin arose early on in evolution as a generalised vasopressor and then acquired an anti-diuretic function as its (ancestral V1) receptors became concentrated in the pre-glomerular vasculature. The anti-diuretic effect of AVT teleost fish resides in its abilty to constrict glomerular vessels, reducing GFR and “de-recruiting” glomeruli so that substantial sub-population become temporarily non-filtering.

Later, in part as a consequnce of gene-duplication events, the ancestral vasotocin system gave rise to divergent oxytocin and vasopressin signalling systems. As V2 receptors arose in tetrapods, vasotocin acquired the distinct anti-aquauretic function that has become its predominant function in man. In frogs, AVT came to regulate water exchange with an aquatic environment through the skin. In similar fashion, vasotocin and vasopressin respectively came to regulate water exchange with a hypotonic urinary fluid in toad bladder or the mammalian kidney.

The dual functions of AVP

In higher vertebrates, the antidiuretic hormone is either arginine vasopressin, AVP (in most mammals) or lysine vasopressin (LVP) in (in pigs), where arginine or lysine are the 8th amino acid respectively. In humans, AVP is synthesised in the hypothalamus in response to changes in extracellular tonicity and released into the circulation by the posterior pituitary. AVP signals through V2 receptors in the medullary collecting duct to insert water channels into the apical membrane of collecting duct cells. This provides a pathway for water reabsorption from the tubular fluid (down a concentration gradient into the hyper-osmolar medullar interstitium). This negative feedback loop (dehydration –> rise in extracellular tonicity –> AVP release –> increased water reabsorption) is effective, sensitive and - happily - intuitively easy to understand. We understand how it works in health and how it can go awry in disease (such as when AVP release is unregulated in the context of pain, drugs or cancer and we end up with SiADH and hyponatraemia).

However, AVP also signals through V1 receptors in the vasculature to cause vasoconstriction. Here it gets a little bit harder to understand how a single hormone can participate in two negative feedback loops regulating two distinct parameters: tonicity and blood pressure. One could call this a vasopressin "paradox" - analagous to the “aldosterone paradox” whereby aldosterone participates in both volume and potassium homeostasis. (Although the latter makes sound teleological sense, as low-volume states induce aldosterone synthesis which then acts to stimulate renal K+ secretion to counter-act the fall in tubular K+ secretion that accompanies slow tubular flow.)

Resolving the vasopressin “paradox”

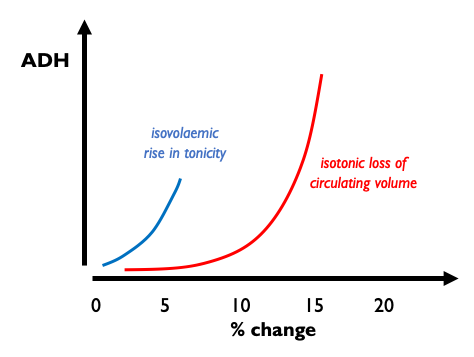

The answer to this apparent paradox is that these two distinct functions are mediated at differernt AVP concentrations. At low physiological circulating concentrations, AVP mediates an exquisitly sensitive negative feedback loop controlling extracellular tonicity by regulating aquaporin expression in the collecting ducts. At high supra-physiological concentrations, AVP induces vasoconstriction. The difference in the sensitivity of these two systems was elegantly demonstrated in a rat model subjected to isotonic or isovolaemic perturbations. AVP release is triggered by very small changes in plasma tonicity whereas circulating volume has to drop by around 10% before AVP levels rise. When hypovolaemia does trigger AVP release however, AVP levels rise to very high levels and induce a profound anti-diuresis.

V1 and V2 receptors exhibit near-idential in vitro affinities for AVP - so how is this difference in concentration-dependency acheived? One prevailing hypothesis is that at low AVP concentrations, any effect of vasopressin on vascular tone is over-ridden by predominant regulatory mechanisms - such as the sympathetic nervous system. Some support for this comes from the observation that low-to-moderate doses of exogenous AVP exert very little effect on blood pressure in healthy controls but induce hypertension in subjects with autonomic failure.

So why doesn’t terlipressin always cause profound hyponatraemia?

Selective vasopressin analogues have been exploited clinically for several decades. Desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin; dDAVP) is an AVP analogue with very high degree of selectivity for V2 receptors. Its binding affinity for V2Rs is several thousand times higher than for V1Rs; dDAVP can therefore be used to treat central diabetes insipidus without exerting an significant pressor effect. (It is also used to treat bleeding disorders due to its ability to liberate von Willebrand factor from endothelial cells.)

Terlipressin (N-triglycl-8-lysine vasopressin) is a prodrug of porcine lysine vasopressin, in which the modification extends its half-life from minutes to hours. Its ability to induce vasoconstriction without also causing a profound anti-diuresis is usually attributed to its selectivity for V1 over V2 receptors. However this argument is much like a vasopressin-deprived kidney: it just does not hold water. The affinity for terlipressin (or LVP) is only around 6x higher for V1 than for V2 receptors, meaning that when used clinically to induce generalised / splanchnic vasoconstriction terlipressin ought to promote water retention and induce hyponatraemia. So why does this not limit its clinical utility?

There are several elements to the answer. First, many patients who are given terlipressin (e.g. for hepatorenal syndrome) are anuric. Therefore they are already maximally susceptible to hyponatraemia and thus invulnerable to the effects of anti-diuretic hormone. If not frankly anuric, then splanchnic vasodilatation will lower effective arterial blood volume and induce AVP secretion and hyponatraemia. (This aberrant physiology is a sign of advanced portal hypertension and a poor prognostic feature.) Again, in this circumstance exogenous AVP can exert only a tiny incremental anti-aquauretic effect. Finally, although not usually limiting, terlipressin-induced falls in serum sodium are actually suprisingly common. In one cohort study, when used for acute variceal bleeding, terlipressin caused hyponatraemia in around two-thirds of patients. So we can conclude that pharmacological doses of terlipressin actually do exert an anti-aquauretic effect in many patients, resulting in a modest reduction in serum sodium concentration. But in most patients in whom terlipressin is prescribed, there are already powerful mechanisms driving endogenous AVP release and anti-diuresis - so the incremental effect may be small-to-negligible.